I’ve never understood the derision that sometimes accompanies the idea of “finding oneself.” I’ve also had problems understanding the notion that some people have that taking off to travel the world, especially for an extended period of time, is somehow an escape or “not facing reality.”

In my opinion, and experience, nothing could be further from the truth. For what, I ask you, is more important in this one journey of life that we have, than discovering who we are, down deep in our core, and what our place in the world is? Is that not the essential meaning of life, and perhaps exactly what we are put here to discover?

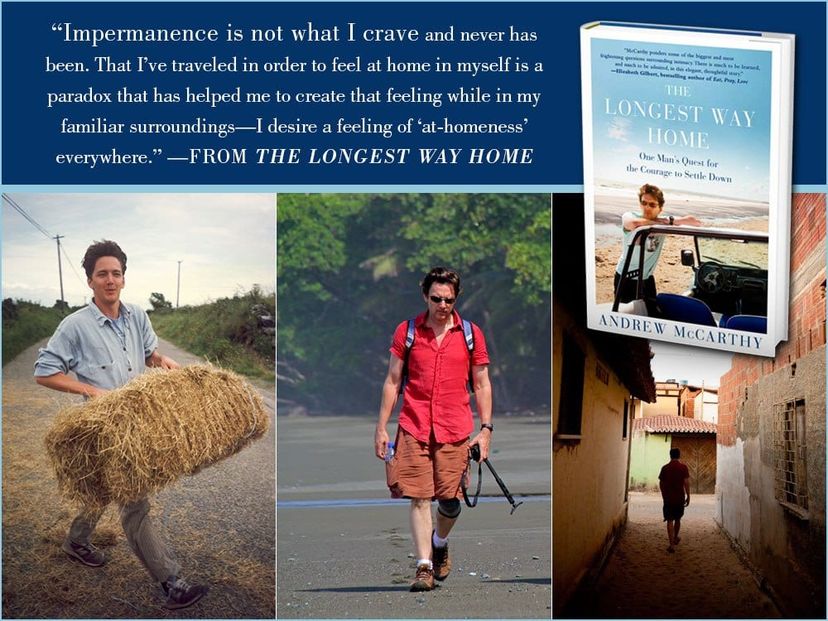

Andrew McCarthy gets it. The actor and director turned travel writer has just released a travel memoir called The Longest Way Home, and that title accurately sums up the roundabout path he has taken in life, across the globe, to figure out the answers to these questions for himself before he takes on a new life with his fiancee. The book jacket states: “Unable to commit to his fiancee of nearly four years—and with no clear understanding of what’s holding him back—Andrew McCarthy finds himself at a crossroads, plagued by doubts that have clung to him for a lifetime. So before he loses everything he cares about, Andrew sets out looking for answers.”

Andrew McCarthy gets it. The actor and director turned travel writer has just released a travel memoir called The Longest Way Home, and that title accurately sums up the roundabout path he has taken in life, across the globe, to figure out the answers to these questions for himself before he takes on a new life with his fiancee. The book jacket states: “Unable to commit to his fiancee of nearly four years—and with no clear understanding of what’s holding him back—Andrew McCarthy finds himself at a crossroads, plagued by doubts that have clung to him for a lifetime. So before he loses everything he cares about, Andrew sets out looking for answers.”

In case you’re thinking that perhaps this is just another “soul-searching” journal from a self-absorbed guy who can’t commit, let me set those thoughts at ease. The Longest Way Home is anything but that. It’s really a love story to travel: the way it helps us discover our truest and best selves, the way it can expand our minds and souls and shape us into different people, and the way in which we must do these things in our own selves before we can possibly hope to fully share that self with another.

McCarthy, who is perhaps best known for his “Brat Pack” roles in movies such as Pretty in Pink, St. Elmo’s Fire and Weekend at Bernie’s, is an extremely gifted writer. Both his passion for travel and his second career as a travel writer came about by accident. He grabbed a book that had sat on his bookshelf for months, to read on a routine flight. The book was about one of travel’s classic pilgrimages, the Camino de Santiago in Spain, and the book inspired McCarthy to make the trek. For the first part of the walk, he was “miserable, lonely and anxious.” But then something happened. His fear began to melt, he started to feel at home in himself.

Every step took me deeper into the landscape of my own being,” he wrote.

McCarthy documented this and other journeys just for himself, for a decade before he finally met up for drinks in New York with National Geographic editor Keith Bellows, who finally agreed to look at his writing after a year of cajoling.

I talked with McCarthy about his book and his philosophy on travel.

Can you recall an early travel experience that fueled your passion for travel?

AM: When I walked the Santiago in Spain, you know that changed my whole life, and really got me hooked on travel.

What has the path from actor to travel writer been like for you?

AM: It’s been a parallel career for me; I’m still acting, I just finished acting in a film up in Canada, a television movie that’ll be out at Christmas [Christmas Dance]. It’s sort of become a shadow career, a parallel one, and it’s something that happened completely by accident. I drank the travel kool-aid, as you well know, and it changed my place in the world. I found I was a better version of myself on the road, I was alive in a different way when I was traveling. It really became very important to me.

It was the same with acting, when I was a kid—that became important to me because I located myself, in a way that I didn’t with other things, and that was a surprise to me. It’s been an impractical passion that I’ve followed, in the same way that acting was.

In the book, you express that by nature you are a very solitary person. How does that work when you travel—do you prefer to travel alone, or choose to interact with others on the road or not? Does it hinder you?

AM: By nature I am a solitary traveler; I prefer to go alone, although I have kids now and traveling with them is a whole other experience. It’s great—I take my kids sometimes when I’m working. I did a story on the Sahara and I took my son and I had a big experience with him there.

But I do prefer what happens when you’re alone in the world. I could go places and not hear the sound of my voice for days, and have no problem with that. If I’m writing a story it’s different; if I’m traveling alone for personal reasons, I will probably talk to less people. But when you’re writing, you of course need quotes, and so I’m forced to come out of myself and interact with people in a way that I wouldn’t were I traveling just for myself.

If we’re traveling together, we’re having the experience of each other in a place; if you’re traveling alone, you’re intimate with yourself in the place and that’s a very different experience. I think traveling alone is a really important thing in life and I think people don’t do it for only one reason: because they’re afraid. And I think that’s unfortunate.

Are there people you’ve met on your travels who stayed with you, whom you’ve thought about frequently?

AM: I don’t think we ever know what affect we have on people. Seemingly meaningless encounters are life-changing for some people, and we have no idea how we impact others. I walked the Camino because I happened to pick up this guy’s book randomly in a bookstore. I’ve never spoken to him again, but nothing has ever been the same since I read his book.

What is your travel philosophy?

AM: I do believe that Paul Theroux theory about ‘Go, go long, go far, don’t come back for a long time.’ I think sometimes the more out of touch we can be, the better because I think we cling to our handheld devices the second we get uncomfortable and if we can unplug them, I think that’s a great thing.

Best travel tip?

AM: Asking for help. I try to ask for help even when I don’t need it, when I’m in a foreign place. It opens me up to a connection with the people there; the minute you ask for help, you’re saying to the person, ‘I’m making myself vulnerable before you.’ That’s always been received on my part, I’ve never had anyone say no.

I’m the guy at home, I’ll never ask for help. ‘I know where we’re going, don’t put on the GPS. We’re fine, I know where it is.’ But on the road, it’s the first thing I do. ‘Hi, can you help me?’ When you do that, you open yourself up in a way that makes us sort of right-sized.

In The Longest Way Home, McCarthy shares a strange phenomenon that I’ve often experienced from the non-traveler. “Tough life,” or “Must be nice,” they often say, as if it’s some unreachable thing they can never attain. McCarthy writes, “Travel—especially by people who rarely do it—is often dismissed as a luxury and an indulgence, not a practical or useful way to spend one’s time. People complain, ‘I wish I could afford to go away.’ Even when I did the math and showed that I often spent less money while on the road than staying at home, they looked at me with skepticism.”

He adds that the reasons people give for not traveling are complex and varied justifications.

He adds that the reasons people give for not traveling are complex and varied justifications.

Perhaps people feel this way about travel because of how it’s so often perceived and presented. They anticipate and expect escape, from jobs and worries, from routines and families, but mostly, I think, from themselves—the sunny beach with life’s burdens left behind. For me, travel has rarely been about escape; it’s often not even about a particular destination. The motivation is to go—to meet life, and myself, head-on along the road. Often, the farther afield I go, the more at home I feel.”

Advertisement