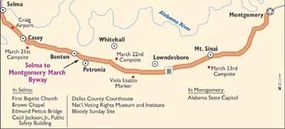

Designated as a National Historic Trail, the Selma to Montgomery Byway has known many facets of history in its years of existence. However, it wasn't until Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., began leading voting rights demonstrations in Selma early in 1965, culminating with the historic Selma to Montgomery March, that the route became internationally known.

After a failed attempt just three weeks earlier, Dr. King marshaled a group of protesters who made their way 43 miles from the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma to Montgomery, giving birth to the most important piece of social legislation of the 20th century. This march helped bring access to the ballot box for many African-Americans in Southern states.

Advertisement

The Selma to Montgomery Byway marks a crucial moment in the campaign for civil rights in the American South. The many landmarks along the way chart the growth of a social movement.

Cultural Qualities of the Selma to Montgomery Byway

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., stood on the platform in front of the stark-white state capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, and gazed out at the crowd of 30,000 people on March 25, 1965. The largest civil rights march ever to take place in the South had finally reached its destination after weeks of uncertainty and danger. Two blocks down the street, at the edge of the vast assemblage, was Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, from whose pulpit King had inspired black bus boycotters a decade earlier. Their year-long display of nonviolence and courage had not only earned blacks the right to sit where they wanted on the buses; it had also started a fire in the hearts of many Americans.

King did not refer directly to the brutal attack by state and local law officers just 18 days earlier. However, that attack, seen on national television, drew the attention of the world to this moment. Less than five months later, the 1965 Voting Rights Act was signed, and African-Americans throughout the South streamed into courthouses to register as voters. They were at last exercising a fundamental promise of democracy, a promise that took our nation 178 years to fulfill.

Historical Qualities of the Selma to Montgomery Byway

African-Americans in Selma formed the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) under the leadership of Samuel W. Boynton, a local agricultural extension agent and former president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Despite stiff resistance from white officials, local activists persisted. Their courage attracted the attention of other African-American leaders. In early 1963, Bernard and Colia Lafayette of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) went to Selma to help the DCVL register African-American voters.

The Selma activists quickly found themselves battling not only bureaucratic resistance, but also the intimidation tactics of Sheriff Jim Clark and his deputized posse. In 1961, the U.S. Justice Department filed a voter discrimination lawsuit against the County Board of Registrars and, two years later, sued Clark directly for the harassment of African-Americans attempting to register.

Fearful that more "outside agitators" would target Selma, State Circuit Judge James Hare on July 9, 1964, enjoined any group of more than three people from meeting in Dallas County.

As protests and meetings came to a virtual halt, local activists Amelia Platts Boynton and J. L. Chestnut asked Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) officials for help. SCLC leaders, following their hard-won victory in Birmingham, had already declared that their next push would be for a strong national voting rights law. Selma offered the perfect opportunity.

On January 2, 1965, Dr. King defied Judge Hare's injunction and led a rally at Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, promising demonstrations and even another march on Washington if voting rights were not guaranteed for African-Americans in the South. Immediately, a series of mass meetings and protest marches began with renewed momentum in Selma and nearby Marion, the seat of Perry County.

Then, on February 18, a nighttime march in Marion ended in violence and death. Alabama State Troopers attacked African-Americans leaving a mass meeting at Zion Methodist Church. Several people, including Viola Jackson and her son Jimmie Lee, sought refuge in a small café, but troopers soon found them.

An officer moved to strike Viola Jackson, then turned on Jimmie Lee when he tried to protect her. Two troopers assaulted Jimmie Lee, shooting him at point blank range. On February 26, Jimmie Lee Jackson died in Selma from an infection caused by the shooting.

His death angered activists. Lucy Foster, a leader in Marion, bitterly proposed that residents take his body to the Alabama Capitol to gain the attention of Governor George Wallace -- a proposal repeated later by SCLC's James Bevel. Bevel and others realized that some mass nonviolent action was necessary, not only to win the attention of political leaders, but also to vent the anger and frustration of the activists.

Even as Jimmie Lee was buried, the idea for a Selma to Montgomery march was growing. By March 2, plans were confirmed that Dr. King would lead a march from Selma to Montgomery beginning on Sunday, March 7, 1965.

Find more useful information related to Alabama's Selma to Montgomery Byway:

- Alabama Scenic Drives: The Selma to Montgomery Byway is just one of the scenic byways in Alabama. Check out the others.

- How to Drive Economically: Fuel economy is a major concern when you're on a driving trip. Learn how to get better gas mileage.

Advertisement